catalogue

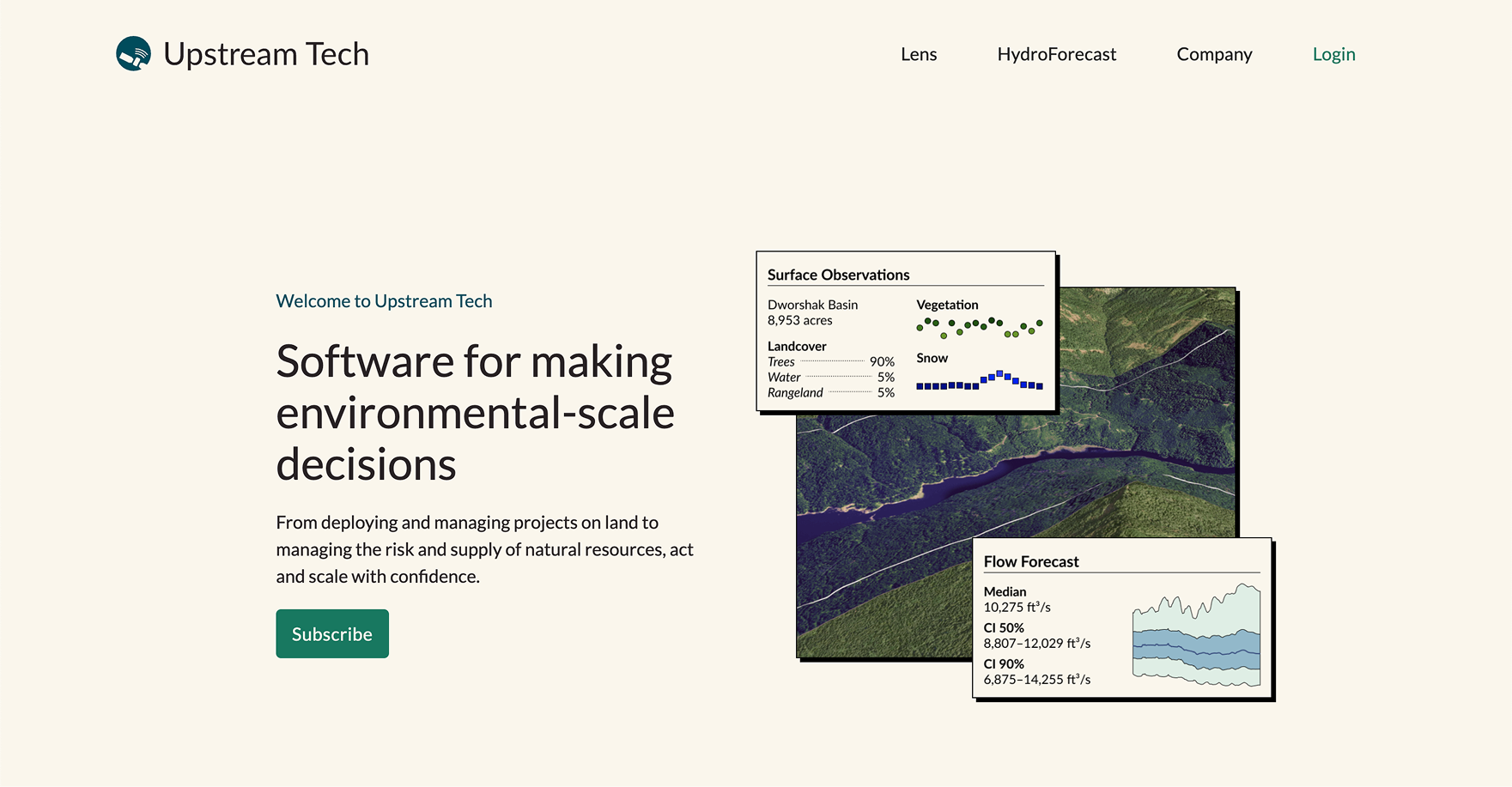

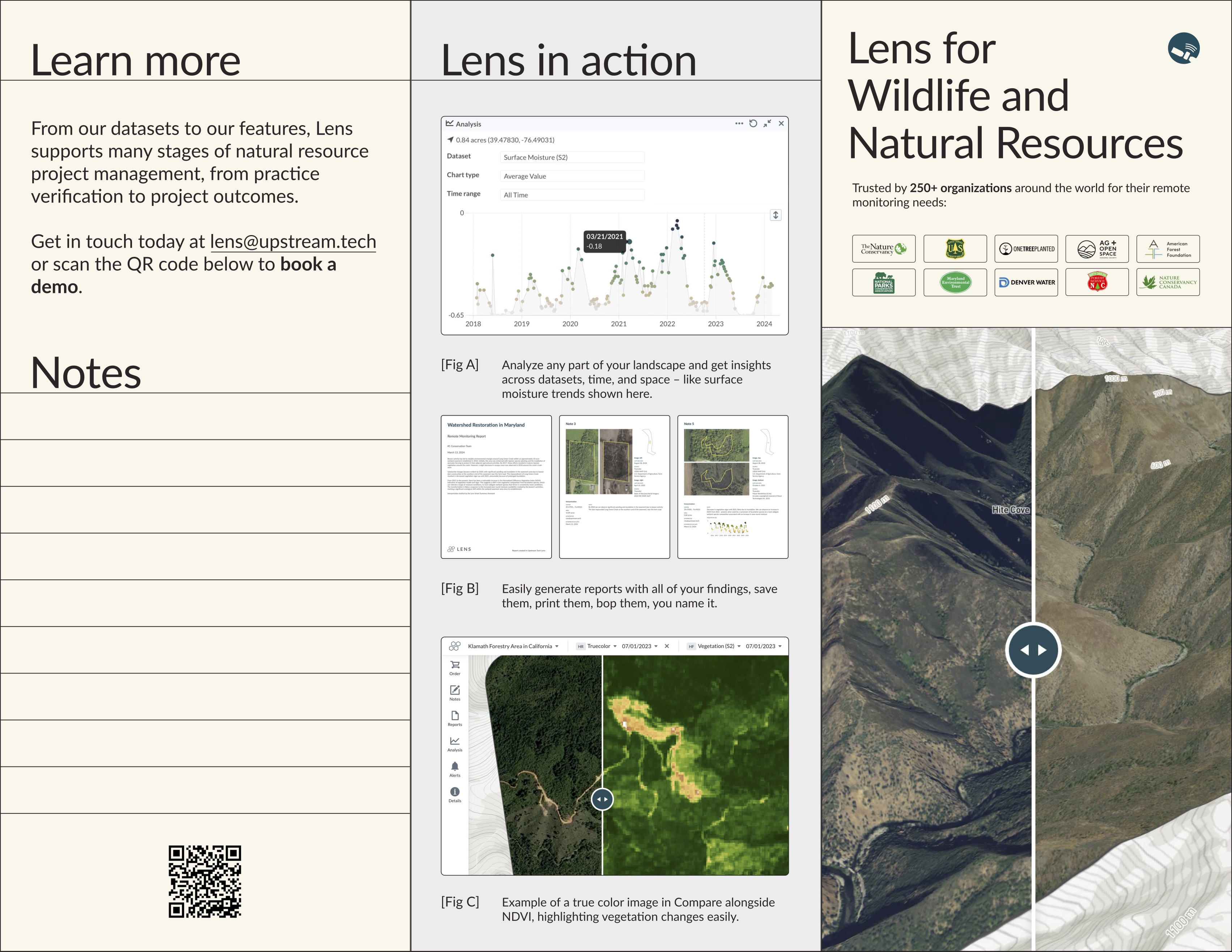

For 2.5 years I led creative marketing and comms for Upstream Tech. The role was multi-hyphenated: I was responsible for design, brand management, copywriting, and content marketing strategy and production. It was a big role in a small team working across the company on two (very) different products.

Find here some examples of this work, though certainly not exhaustive. All creative and media content was made by me in most or all forms - logo design, book design, web development, infographics, copywriting, editing, etc., even motion design for our videos.

Though not featured here, I was also responsible for authoring the company’s first brand guidelines and constantly evolved the brand and product marketing throughout my time there.

As their work looks different since my departure, please refer to these select examples instead.

1] Copywriting, product marketing

Click on the links to view example reading on the company website, or scroll to find design work here.

P.S. The author credit is now anonymized since I no longer work there but trust me – those are my jokes alright.

Case studies

Adding integrity to carbon projects with carbon insurer Kita ↗

Remote monitoring at a national scale with the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation ↗

Interview

On the importance of storytelling for effective nature-based solutions: interview with MaryKate Bullen ↗

Thought leadership

Measuring and monitoring for one of Earth’s key planetary boundaries, biodiversity ↗

Preparing for Europe’s drought with HydroForecast ↗

Remote monitoring for forest management ↗

Product feature

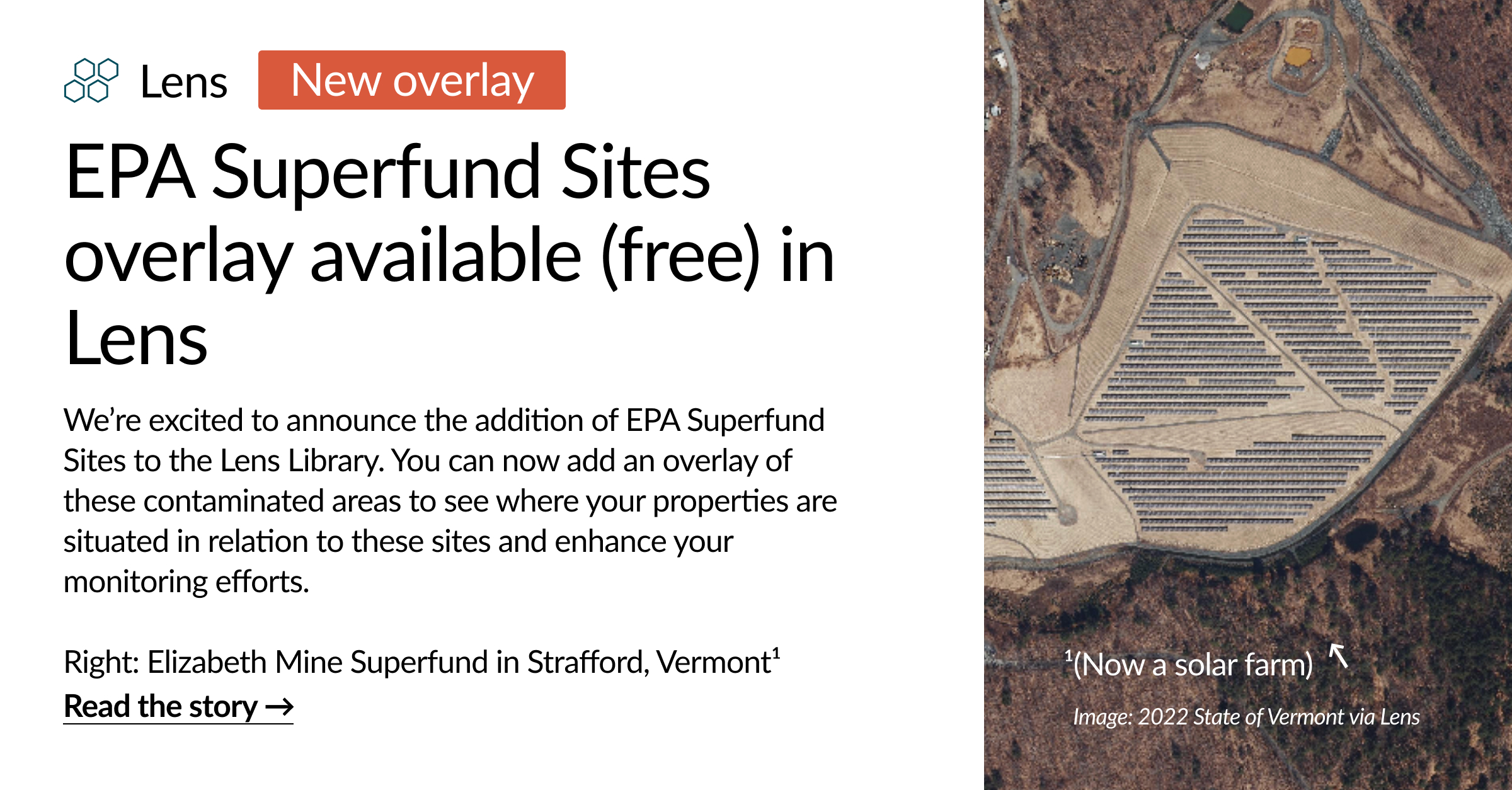

How to easily access up-to-date parcel data and satellite imagery in Lens ↗ plus the graphic.

How AI can be a useful tool for climate and the sciences ↗ – ghost-written. I was the main author but collaborated with engineers and technical staff on content

Announcing Lens Lookout: Automated Change Detection Alerts ↗

Website landing pages

Company website

Much of the product marketing copy on the company website from 2022 to November of 2024, collaborated on with relevant product teams. Heads up as some of this has changed since my departure, but please see other product marketing examples in the design section below.

2] Motion design and video editing examples

Examples where I created the motion design assets, logos, interactions and owned video editing and production. Typically the script was co-written and a collaboration between multiple teams and people, and audio is all in-house.

3] Brand design assortment

The Hewlett Foundation commissioned me to interview four key leaders in the environmental field representing four separate organizations. The assignment involved prepping questions and prod logistics, travel to each state, and building the story over a few days.

Final project deliverables included an in-depth interview of each leader, an article, photography for print and digital media to accompany the story.

The following are examples of the story and images for two/four stories.

Becca Aceto for Artemis Sportswomen

Becca Aceto is a hunter, angler, conservationist, storyteller, and all-around public lands steward living in Boise, Idaho. At 28, she’s working to conserve the wildlife and public lands that give her food, peace, and beauty while making sure that the voices coming to the conservation table are diverse, new, and readily welcomed.

Originally from the suburbs of southwest Ohio, Aceto credits her childhood as the inspiration for her conservation work today. Her parents encouraged Becca and her siblings to explore: “They would kick us out the door after school to go roam until nighttime,” she remembers fondly. The local park offered some of her first experiences outside: fishing bluegill with a simple stick or searching for snakes in the brush.

After graduating from the University of Kentucky with a degree in natural resources, Aceto began her journey into conservation. She worked as a naturalist at the Sawtooth Interpretive and Historical Association, a wilderness ranger with the Payette National Forest, and then spent three years as a field biologist with the Sawtooth National Forest. In 2017, she began hunting. “One of the big turning points in my life was when I started to hunt. It added this incredible layer to what I thought was a very full life spent in the outdoors.”

Today, Aceto is an Ambassador for Artemis, an initiative of the National Wildlife Federation that seeks to create space for women to support one another as hunters and anglers while uplifting their voices to the forefront of the conservation movement. During the week, she works as the communications and outreach coordinator for the Idaho Wildlife Federation.

Estrada: Why is Artemis and its mission important? Why do the voices of women matter?

BA: Artemis is crucial for playing the role of a safe, welcoming, encouraging place for women who wish to wade into hunting, fishing, and conservation, or who want to grow within the community. It’s a community where immense individual growth can happen and where the hopes for the future vision of the conservation world can be modeled. As unique individual voices and powerful, supportive, passionate collective voices, the women of Artemis (and conservation in general) bring with their voices a new narrative of progress, inclusion, and passion. Some of the strongest, most unique, and forward-thinking voices I know in conservation are those of women, not because of their gender, but because they are fiercely passionate about this work. That spirit right there is what Artemis embodies.

Estrada: What’s a goal you have for your work, your career?

BA: I hope that I continue to be someone who fights for the places and the experiences that have given both my professional and personal life deep meaning. A windblown ridgeline above an alpine lake, a vast sea of sagebrush rising up to meet a mountain range of 12,000 foot peaks, a free-flowing, wild river with osprey and bald eagles above, trout and salmon within—these are the landscapes that have and will continue to shape me; places that I share with anyone willing to join in the hopes that their own lives will be changed, too.

On my watch, during my career, I hope the wins for the land and wildlife always outnumber the losses. And my deepest hope is that humanity continues to foster this appreciation through education, enjoyment and shared experiences because in the end, the more people who care, the better chance we have to preserve wild things and wild places long after I’m gone.

Making outdoor recreation more inclusive: Interview with Outdoor Afro’s Antoine Skinner

With a 70-pound pack in tow and a camera clipped to his chest strap, Antoine Skinner wades through the warm, sandy trail. The temperature, 100 degrees, is rising steadily in the Arizona summer, and he’s only just begun the seven-mile hike into the red rock canyons of Coconino National Forest.

Near some high brush, he rounds a bend and sees a group of early morning hikers approaching. Skinner notices them first. Sometimes he’ll make a noise to alert folks of his presence but many times he lets the quiet be. As they’re about to come face to face, Skinner gives a common trail-friendly greeting, “Good morning.” The fellow hikers look up and, for a small moment, appear stunned by whom they see. After their short pause, they recover and eventually return a curt, “Howdy,” before continuing on.

For Skinner, the moment isn’t outstanding. Like the Arizona heat, it’s normal, even expected. On the trail, on that day alone, he’ll experience some version of this same reaction from white hikers at least a dozen times. Often, they’ll suddenly notice him, their spine and shoulders will slightly snap back, and a surprised, confused, maybe even fearful look will flash across their faces, proceeded by one of two endings. Either a quick attempt to take the previous reaction back — facilitated by a greeting — or awkwardness. The awkwardness that comes with a continual gawking as Skinner passes by, unfazed and unsurprised.

At 42, and after spending almost his entire life in the wild, Skinner isn’t waiting to be accepted. He’s traversing into the backcountry, having a great time, and being unapologetically Black while at it.

On most weekends, Antoine Skinner hits the trails. Maybe it’s a 18-mile backpacking trip up and down Mount Baldy, or a heat acclimation hike at South Mountain in Phoenix. For the past six years, it’s meant exploring the wonders that the Southwest has to offer, from red rock canyons to blistering deserts filled with towering saguaros.

Skinner grew up in Philadelphia, where his love for nature started early. When his older sister joined the Girl Scouts, he remembers telling his mom that he wanted to join too — it looked fun. So, she placed him in the Cub Scouts. He rose to the top rank and then joined the Boy Scouts, where he eventually reached the highest rank of Eagle Scout as well. From then on, he did it all: kayaking, lifeguarding, whitewater rafting, you name it. He credits his time with the Boy Scouts as one of the main impetuses for his love of nature today.

In 2017, after two years of volunteering as a wilderness mountain rescuer, Skinner became the Arizona outings volunteer leader for Outdoor Afro. Outdoor Afro started as a blog in 2009 by Rue Mapp, founder and CEO of the nationwide not-for-profit. The mission of Outdoor Afro directly centers on the Black experience in the outdoors. The organization aims to proactively meet Black people where they’re at in their varied relationships to nature. As Skinner notes, if nature means taking a walk around a lake — perfect. If it means kayaking —that’s perfect, too. The goal is for Black people to heal. To reconnect.

National parks and the concept of public lands were not created in a time of equality. When Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872 as the first national park, it required that the Nez Perce be forcibly removed from land first. Jim Crow laws were in effect from 1876 to 1964, mandating racial segregation that severely and wholly impacted the lives of African Americans, including how they could recreate, or how safe they could feel while recreating, especially in public spaces like parks. The parks remained segregated through the 1940s, and some of them longer. And even if African Americans weren’t recreating, it wasn’t safe to simply be Black. Last September, a commemoration was held for Bowman Cook and John Morine, two Black men who were lynched in Jacksonville, Florida in 1919, a mere three years after the National Park Service was founded in 1916.

There’s trauma for Black bodies in nature, trauma that’s been passed down through generations. Outdoor Afro actively addresses the trauma through community, safe space, and getting Black people together to heal one another and their relationship to nature.

Being an Outdoor Afro outings leader is like being a teacher: the work never really ends. Luckily, for folks like Skinner, it doesn’t need to. The outdoors is the one place that’s made him feel most at home, and he wants to make sure that all Black people can experience that same liberation, joy, and happiness outside.

For a period of over 4 years, and likely still counting, I worked with climbing coach/legend Emily Taylor. For this piece, we worked together to tell the story of her experience in the climbing world as a Black and queer woman for The Alpinist, issue 66.

October 10. 2003: The midday sun blanketed the face of Tu-Tok-A-Nu-La (El Capitan) as Emily Taylor moved up the wall with intention. With her fingertips, she pulled on tiny ledges, and she pressed her toes hard against the granite. She was high up on the Nose, a line that winds its way 3,000 feet up the prow of the southwest face.

~

WITH THOUSANDS OF FEET of air beneath her shoes, Taylor breathed in the crisp autumn air. When she topped out on the thirty-first pitch, she became the first known Black woman to ever complete the route.

Born in the 1970s at the Camp Pendleton base, Taylor was raised by her father, one of a few Black colonels in the US Marine Corps. Her father raised her with the values of "self-reliance, respect and determination," Taylor says. They moved often, relocating from Côte d'Ivoire to Okinawa, and many states in between California and Florida. "Learning to adapt to change was a way of life," Taylor states. After graduating high school, Taylor attended Winthrop University in South Carolina to study music. In her junior year, her father passed away. Suddenly Taylor found herself trying to manage her grief and school-work, as well as homecare for her grandmother, who lived states away.

The summer after her father died, Taylor signed up for a two-month-long Outward Bound course. The second week of the expedition, she and other participants learned to fashion a Swiss Seat (a rappelling harness) out of webbing. Wearing hiking boots, Taylor handily finished and cleaned a 5.10d; she reveled in experiencing the warm, red rock for the first time and her newfound strength. When she got home, she immediately bought climbing gear and started training and working at Charlotte Climbing Center.

After college, Taylor moved to Atlanta, where she worked at a climbing gym part-time as she began her career as an experiential adventure-based facilitator at a children's hospital. In 2001 a friend of Taylor's was denied entrance to the climbing gym because she was in a wheelchair. Taylor quit working at the gym that day. Soon after, she moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where her passion for coaching ignited. She became determined to change the system, and her career as a climbing coach got its start. She helped design a harness for paraplegic climbers known as Para-Feet and created instructional and safety videos for climbers with hearing impairments.

As a Black and queer woman, Taylor is drawn to coaching climbers who, like her, are underrepresented in the climbing community. Racist, sexist and ableist comments were frequent at both the gyms and the crags she visited. In 2003 Taylor moved to Atlanta to work as a climbing coach.

There, she spent the next two decades working with Black and Brown youth climbers and athletes with disabilities, independently incorporating equity and inclusion throughout her work.

Taylor's approach with her students is always twofold: teach them how to move on the wall and how to move through society. In 2015 Taylor led a group of kids on a climbing trip in West Virginias New River Gorge. One day they went to the river to relax and found a few white men hanging out. "One of them goes, 'Who's this n--- with all these children?'" Taylor recounts. "I froze. Suddenly I had to make a choice: leave with my students, stay and go in the water, or in some other way react." The scene was all too commonplace. "But this is a reality," Taylor says. "There are places in this country where I can't go and feel safe without having white friends accompanying me."

In 2016 Taylor moved with her daughter to the Bay Area, where she founded Brown Girls Climbing, a team of all Black and Brown identifying girls. The organization began, Taylor says, because she saw "a need [to] create a safe, inclusive space for the most marginalized population in rock climbing." For Taylor, that's a space for the girls to be, and become, unapologetically themselves. It's about being Black and scaling mountains every day, she says, and showing the next generation of Black climbers, including her daughter, how to thrive.

"To be pro-Black is not to be anti-white. Coaching Black and Brown children requires a radical awareness, cultural competency and communal connection, as well as the simple ability to see and value the embodiment and vitality of Black lives," Taylor says. "What it's gonna take for this sport to move forward is for white folks to recognize that there's a lot to unpack here. There's trauma around rope, trauma around bodies. To say 'trust me and sit back' is more than a climbing routine," Taylor says. "It's about honoring the voices of my ancestors and our collective liberation."

In 2019, American Rivers commissioned me to create a series that centered people whose work centered around rivers in the United States, titled Voices from the River. Featured here is one such story and interview featuring Mary Helen Niccolini.

Mary Helen Niccolini extends her arms out, outlining Marsh Creek's meandering path from the highway bridge to where it presumably ends, unseen, at the Bay. As we walk down the trail, she points out an important fact: the restoration of Marsh Creek is not a quick project. It won't start displaying signs of completion until years down the line. When it is done, the community will enjoy the fruits of a beautifully restored creek, and the native flora and fauna will benefit from thriving, native habitat. The paved trail that parallels the creek will also connect Brentwood to Big Break Shoreline, a six-mile path for the community to explore.

However, as any ecologist knows well, habitat restoration – and particularly creek restoration – takes time. Time from nature, and hard dedication from folks like Mary Helen who are committed to projects that go beyond the ephemeral and invest in the longterm. Luckily, it’s this component that has driven Nicolini throughout her career. Her passion lies in connecting science with people, and using practical solutions that will benefit both the environment and the local community that depends on it.

Nicolini is composed and brilliant; a scientist and aquatic biologist who is precise, cheerful, and passionate. She lights up when she begins chatting about her love for the ocean and science, as she does recalling some of her first memories outdoors. As a child, she was very aware of the changing seasons. How fall’s warmth diminished into winter and how the crops could no longer grow. Through her family, she recounts fishing and spending a significant amount of time in Santa Cruz, at the ocean. Stunningly, at only four and during her first experience in the water, she nearly drowned.

“A wave caught me and tumbled me in,” she says happily. “My parents thought I’d be scared of the ocean for life. I was startled but I actually loved it.”

A 2nd-generation Mexican American, Mary Helen was raised in Merced, the youngest of 7. Her closest sibling still 9 years apart. Her father was a foreman on an almond ranch, and her mother a homemaker who worked during the summers, packing tomatoes. Beyond, her grandparents were migrant farmworkers who moved with the seasons and the crops, from Palm Springs to Santa Rosa. They immigrated to the United States in the 1910s and, through their dedication to the land and environment, laid the foundations for Mary Helen's lifelong work and approach.

At 59, Mary Helen’s path is familiar to many women of color in STEM, especially considering that she went to college in the late 70s. She recalls being the “only one” studying Marine Biology at UC Santa Cruz, i.e. the only Mexican-American woman in her major, and the offhand comments that sometimes came with it. In one of her most vivid experiences, she remembers being approached at a festival and asked why she wasn't with her own people.

And yet, while her presence in the programs was sometimes seen as an anomaly, she didn't think so. "I didn't grow up seeing myself isolated from nature. I saw that I was a part of it,” says Nicolini. Indeed, her connection to the land from an early age resonates throughout her work, especially in how she favors projects with big scope and longstanding commitment. In other words, projects with positive impacts that might not even come to fruition in her own lifetime.

When you look at Mary Helen’s repertoire of work, it’s clear that her approach is not only holistic — it’s deep-rooted. It seeks to positively affect the lives of people and wildlife through science.

After graduating from UC Santa Cruz, she went on to study the effects of stormwater runoff on aquatic life for her Master’s. She then looked to become more involved with people and science, and joined the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic. The goal there was to develop a low tech method of aquaculture that might support the livelihood of local fishermen. Afterward, she worked throughout the Bay Area as an aquatic toxicologist, as a graduate student at UC Berkeley, and most recently worked with Friends of Marsh Creek Watershed, which led her to her current job today.

Presently, Mary Helen works as a contracted Aquatic Ecologist for American Rivers, helping lead the design and monitoring of Marsh Creek. As part of her position, she leads student and volunteer groups – understanding that effective restoration projects must also mean involving the community and the next generation of stewards.

Through the student groups, who are primarily students of color, she is able to teach them about the value of creeks and restoration, while providing hands on experience that could influence their own trajectory later. In the fall, Chinook Salmon run through the creek, so the students are able to directly learn how healthy habitat lead to healthy wildlife. The investment ends up being twofold: both in the creek and in the students who might one day become an aquatic biologist like Mary Helen.

It means the most to know that the work she’s doing will positively affect the local community for years to come. In considering the future, it’s also deeply important that she’s working to impact the environment positively, and leave a lasting impression for her daughter, who’s currently in high school.

“After all, that’s where it all comes back. Being able to leave something that’s going to be around for a long time.”

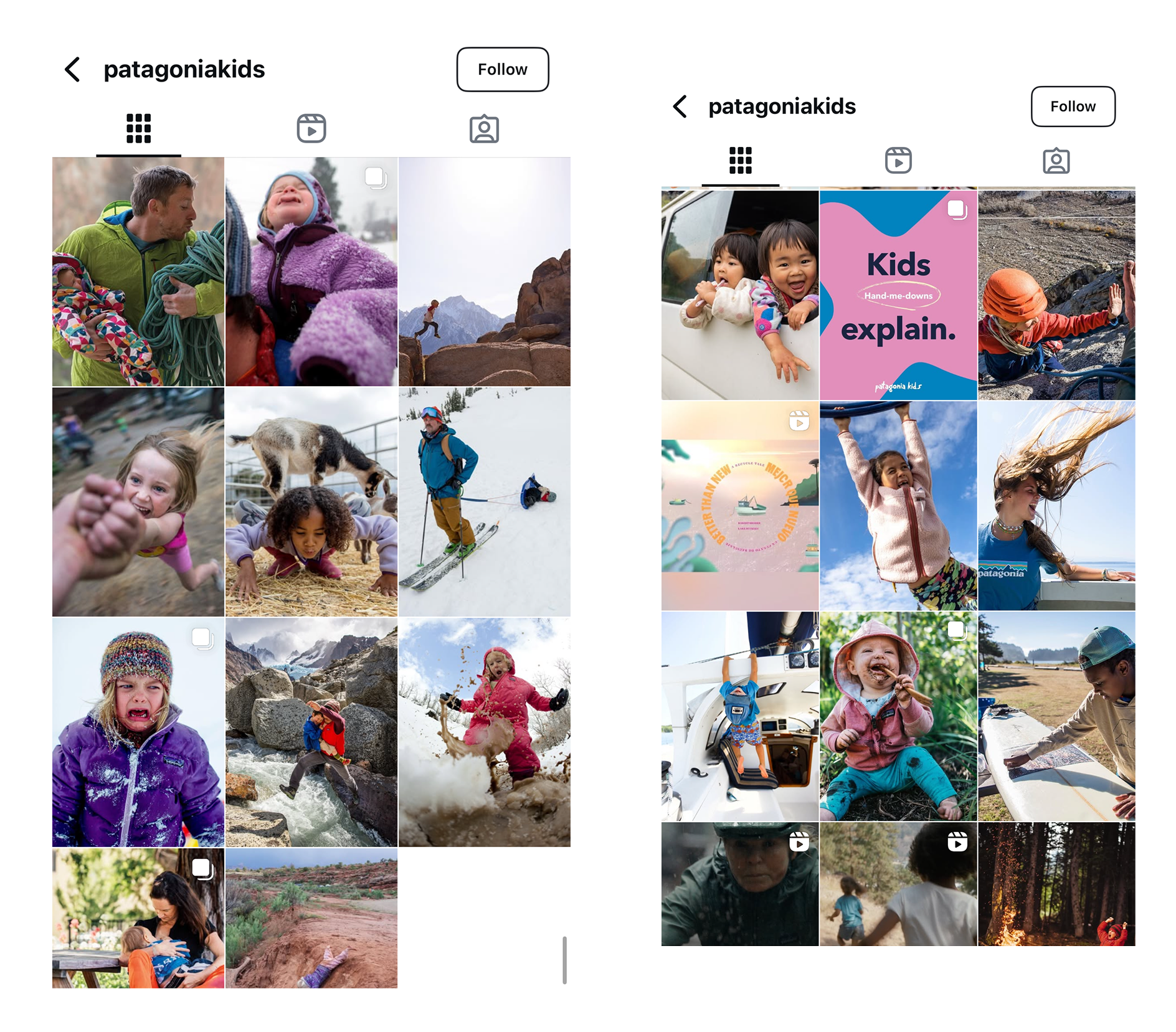

I’ve worked alongside Patagonia for many years and many, many projects. From staff global photo editor to consultant to writing, photo, and this project here: Creative direction and photo editor for the launch of the Patagonia Kids Instagram account, a project years in the making.

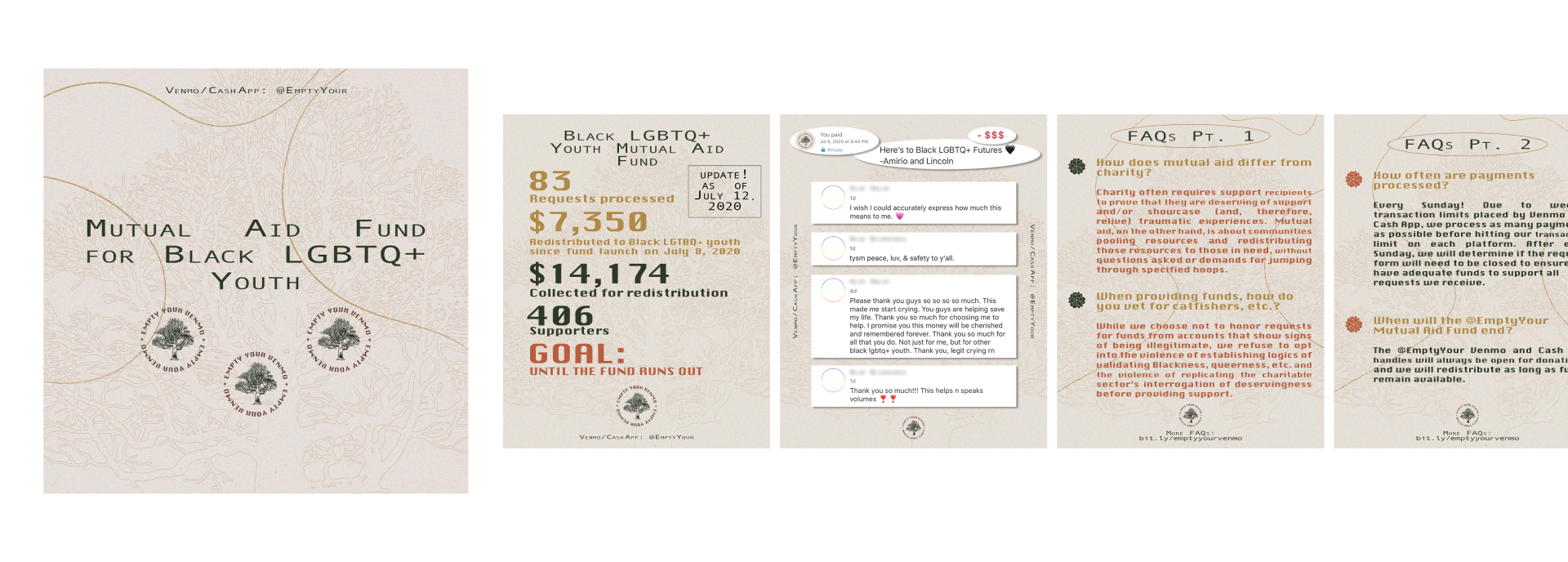

Creative direction, branding and identity designer, involving social graphics, visual identify for the web design, and minor motion design elements for social, as well. Assets were picked up by media and other outlets. Outcome: over $30,000 raised in only two months and re-distributed to Black LGBTQ+ youth across the country.

Sample slides from the Instagram posts.

I’ve been honored to be interviewed and featured for my work through different outlets. One such example comes from 2022, when I was a featured cyclist for Riese & Muller’s print publication featuring four cities in the world: Paris, San Francisco, Copenhagen, and London. It was an eventful shoot spanning a few days in San Francisco, where I lived for a decade before moving to NYC.

The following shows some pictures that didn’t make the edit. Also missing is the interview and spread.

Photographer credit: Lars Schneider on a Leica.

Parts from the interview

R+M: How would you describe your relationship with cycling?

Em: It began as a kid, but I got really into it starting in college. I wanted to join the triathlon team and so I borrowed a heavy steel bike to do my first one. I eventually bought the bike and used it until after I graduated. Then I wanted to train for an Ironman and invested in my first real road bike. I moved to the Marin Headlands and I biked nearly every day over the Golden Gate Bridge to work. As I rode every morning through windy sunrises and came back in the evenings through dense bone-chilling fog, I became enamoured not just with cycling but with the calmness of the solo commute. While folks were locked in traffic, I would happily glide towards the mountains and home. For a long time, I didn't have a car in San Francisco and I would bike everywhere - to get my food, shop, to see friends, to go to work.

I first got in touch with the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition in 2019 while on assignment for an entirely different project. What began as an interview of one leader eventually evolved into a long-lasting work relationship, where I was entrusted to build the Coalition’s media gallery and meet more of their leaders and people. The relationship wove in many different projects and experiences out in Bears Ears. I was honored to be a part of it.

At the start of 2020 (pre-pandemic), I wrote, designed, and published 'Storytelling Sovereignty', a zine about the importance of having the storytellers be representative of the community whose story is being told.

The zine was picked up by places such as The Whitney Museum, Wendy’s Subway, and Printed Matter.